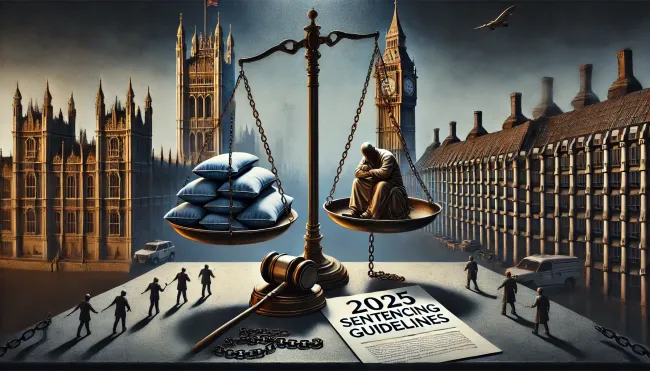

As changes to sentencing guidelines grow imminently closer, questions arise over whether they are suitable to the foundations and priorities of a justice system that must be strong. Now more than ever.

On 1 April 2025, the Sentencing Council’s new guidelines will come into effect, fundamentally changing how courts sentence offenders in England and Wales. Judges will now be encouraged to consider an offender’s personal circumstances beyond just motivation for the crime committed—including their ethnicity, cultural background, gender, and socioeconomic status—when determining punishment.

Supporters claim these changes address systemic inequalities, but critics warn that this approach risks undermining the principle of equal justice. The guidelines introduce a clear division in sentencing, where certain offenders may receive lighter punishment based on who they are, rather than what they have done.

At stake is a fundamental question: Should sentencing be blind to identity, or should courts apply different standards to different groups?

What Do the 2025 Sentencing Guidelines Change?

Under the new rules, judges are encouraged to obtain Pre-Sentence Reports (PSRs) for offenders from specific groups before sentencing. These groups include:

Ethnic minority offenders

Young adults (18-25 years old)

Women (particularly pregnant women and mothers)

Transgender offenders

Judges will be advised to assess whether a defendant’s background contributed to their crime and whether prison is necessary.

This shift reflects a growing trend in policymaking: treating crime not just as an individual act, but as a symptom of wider social inequalities. Proponents argue this ensures fairer outcomes, but the reality is that it introduces identity-based leniency, where offenders from certain backgrounds are more likely to avoid jail.

Senior legal figures and ministers have raised concerns that the new guidelines put the interests of criminals above victims and could further erode trust in the justice system.

Are Victims Being Overlooked?

Victims of crime can submit Victim Personal Statements (VPS) detailing the physical, emotional, and financial harm they have suffered. In theory, these statements should influence sentencing. In practice, they are often ignored.

A 2021 Oxford University study found that only 43% of victims were even invited to submit a VPS.A 2022 report by the Victims’ Commissioner found that judges rarely referenced VPS in sentencing remarks, despite victims believing these statements should carry weight.

Now, with the offender’s background being prioritised in sentencing decisions, victims are likely to feel even more disregarded. If sentencing is tailored to accommodate the criminal, where does that leave those who have suffered at their hands?

A Two-Tier Justice System?

The 2025 Sentencing Guidelines cement a two-tier approach to justice.

Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood has stated:

“As someone from an ethnic minority background myself, I do not stand for any differential treatment before the law, for anyone of any kind. There will never be a two-tier sentencing approach under my watch.”

But differential treatment is exactly what these guidelines promote. They create a legal hierarchy, where some offenders receive leniency because of factors entirely unrelated to the crime they committed.

Critics argue that:

- Justice should be based on the crime, not the identity of the criminal.

- Victims suffer the same harm, regardless of who the offender is.

- Public trust in the justice system collapses when sentencing is seen as unfair.

Advocates of these guidelines claim that certain offenders face “systemic disadvantages” that should be accounted for. But where does this end? Should a working-class white man from a deprived area be treated differently to a middle-class offender from a minority background? Should a woman who commits fraud receive a more lenient sentence than a man who did the same?

Once sentencing becomes about identity rather than individual responsibility, justice is no longer impartial—it becomes political.

The Equality Act: Driving Unequal Treatment?

Professor Matt Goodwin has warned that Britain is increasingly becoming a nation of managed outcomes rather than equal opportunities. He argues the Equality Act 2010, far from ensuring fairness, has justified preferential treatment within institutions, including the courts. Goodwin explicitly advocates for the repeal of the Equality Act, suggesting its existence perpetuates a two-tier society and institutionalises unequal treatment.

The Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED)—a key part of the Equality Act—requires public institutions, including the judiciary, to ‘consider the impact’ of their decisions on different groups. This creates an expectation for courts not only to prevent discrimination but actively engineer “fair” outcomes—even if this means treating offenders differently based on identity. The 2025 Sentencing Guidelines reflect this mindset, explicitly promoting identity-based sentencing rather than equal treatment under the law.

While scrutiny of government legislation is essential, repealing or condemning the Equality Act is not straightforward and likely creates further complications. Growing public resentment and mistrust in our legal systems stems from supposedly solid frameworks bending too readily to identity politics and manipulation. Like the controversial two-tier sentencing guidelines, repealing the Equality Act would risk further exploitation by individuals pushing their agendas. The Act originally unified laws such as the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 and Disability Discrimination Act 1995, explicitly aimed at ensuring legal clarity and preventing misinterpretations now frequently occurring.

Further evaluation and amendments to the Equality Act may indeed be necessary, but legal clarity and comprehensible inflexibility should remain paramount. Historically, violent offenders have manipulated courtroom sympathies; weakening this legislation risks further empowering those who seek to weaponise the legal system for personal advantage. A government and justice system must remain fair, strong, and consistent, refusing to pander or abandon fundamental principles. Without meaningful revisions, Britain risks continuing down a path where fairness is undermined by identity politics.

What Does the Research Say?

Proponents of identity-based sentencing argue that certain groups receive harsher punishments due to discrimination. But research suggests that when factors like prior convictions and plea decisions are accounted for, disparities largely disappear.

1. Do Black Men Receive Harsher Sentences?

A 2020 Cambridge University study found that while Black offenders were more likely to receive custodial sentences than White offenders for drug offenses, this gap was significantly reduced when controlling for previous convictions and aggravating factors.

A 2022 University of Manchester study found that racial disparities in sentencing were primarily explained by case complexity and plea decisions—not racial bias.

2. Are Women Treated More Leniently?

A 2023 University of Bristol study found that female offenders received 36% shorter sentences than men for comparable crimes.

Current sentencing guidelines already favour women, particularly pregnant offenders. The new 2025 guidelines expand this further, meaning that women will now have even greater chances of avoiding custody than men.

3. Does Poverty Impact Sentencing Outcomes?

A 2021 University of Sheffield study found that defendants from deprived backgrounds were already more likely to receive community sentences rather than prison.

This suggests that socioeconomic status already influences sentencing—without the need for explicitly codifying identity-based leniency into law.

What Are the Consequences?

The 2025 Sentencing Guidelines could have severe consequences for Britain’s justice system:

Reduced deterrence – If offenders believe their identity will protect them from severe punishment, crime may increase.

Loss of public confidence – If victims feel that criminals are prioritised over them, trust in the justice system erodes.

Sentencing inconsistency – If courts impose different punishments for the same crime based on identity, the justice system becomes arbitrary.

Justice must be impartial—it cannot be adjusted based on who the offender is or what group they might fall into.

Conclusion: Time to Rethink Sentencing Priorities

The 2025 Sentencing Guidelines represent a significant shift in how Britain applies justice. By prioritising offender background over victim harm, they risk turning the justice system into an extension of identity politics.

Justice should be blind. Punishment should reflect the severity of the crime, not the background of the criminal.

Victims must not be sidelined. Their suffering must carry more weight than an offender’s “lived experience.”

The law must apply equally. Identity should never dictate sentencing outcomes.

As Matt Goodwin warns, as long as the Equality Act remains unchanged, policies like these will continue to creep into every institution.

The government now faces a choice: restore fairness, or allow sentencing to be permanently divided along identity lines.